Celebrating the Medicine Class of 2021 with Erik Mandawe

April 20 was an important day for hundreds of medical students across Canada. In 2021, it was the date when students learned to what residency programs they matched.

April 20 was an important day for hundreds of medical students across Canada. In 2021, it was the date when students learned to what residency programs they matched.

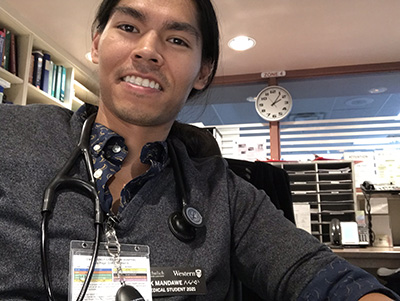

For Erik Mandawe (ᐱᔦᓯᐊᐧᐠ) the day signified much more.

It represented a milestone in his journey to continue pursuing his passion for helping people and making institutional changes to improve health outcomes for Indigenous communities; all while staying true to his personal vision of healing for himself, his family and his community.

From the beginning of his medical school studies, Mandawe lived his truth.

He knew that medical school was going to be a different way of relating to others around him. He also knew that he was on the right path to using his gifts as an artist and his identity as a Bush Cree person in his role as a doctor.

He recalls feeling conflicted after receiving an invitation to the annual White Coat Ceremony, an event that marks the beginning of medical school. He wondered how he could participate in an event centred on an object that, in the eyes of many Indigenous people, serves as a tool of colonialism.

He considered how he could put himself into the symbolism while remaining true to himself and his vision.

Working with his mother, Ramona Dunn, they wove together intricate and connected images that reflected and honoured his culture and community. The result was a beautifully embroidered tapestry of symbols sewn into his white coat representing his community, the Beaver Lake Cree Nation in northern Alberta, his adoptive clan, the Wolf Clan, and his family colours. It also included two thunderbolts to represent his name, Piyesiwak, which means Thunder.

Working with his mother, Ramona Dunn, they wove together intricate and connected images that reflected and honoured his culture and community. The result was a beautifully embroidered tapestry of symbols sewn into his white coat representing his community, the Beaver Lake Cree Nation in northern Alberta, his adoptive clan, the Wolf Clan, and his family colours. It also included two thunderbolts to represent his name, Piyesiwak, which means Thunder.

Mandawe says that the thunderbolts placed side by side on the coat, also represented The Two Row Wampum, which is one of the oldest treaty relationships between the Onkwehonweh (original people) of Turtle Island and European immigrants. The Two Row is a foundational philosophical principle, a universal relationship of non-domination, balance and harmony between different forces.

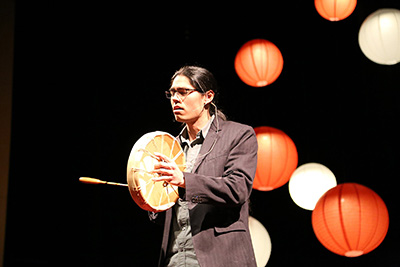

A musician, performer, and visual artist, Mandawe spent his first year of medical school also serving an annual term as London’s inaugural Artist in Residence, through the London Arts Council. It was an important year for Mandawe, who says that sharing his art, participating in public performances and collaborating on visual pieces validated his understanding of his role as an Indigenous health care provider.

The arts provided Mandawe with an important pathway for creativity and expression. However, with the challenges of medical school and the need to stay physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually healthy in the process, he found himself seeking the wisdom of elders and inspiration from the land.

The arts provided Mandawe with an important pathway for creativity and expression. However, with the challenges of medical school and the need to stay physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually healthy in the process, he found himself seeking the wisdom of elders and inspiration from the land.

“There is a teaching that I walk with - that our environment shapes the way we think,” he said. “This is important, because where we physically spend most of our time ultimately shapes the ways that we’re thinking. And I need to know how the information I’m learning in the classroom relates to the land, because that’s what I want to shape my thinking.”

He recalls a time, when he was studying the respiratory system that he was able to make that connection. While presenting at a medicine conference in Alberta, he went mountain climbing. He saw in snow covered-trees the relationship between the lungs and those trees. In the leaves clinging to the branches, he saw the alveoli – the tiny air sacs in the lungs that take in the air a person breathes – to form a symbiosis between the trees and people.

“As a Cree learner, seeking out experiences like that as part of my training have been important. It needs to make sense to me in this way. It’s about our relationship to everything around us, and how we are all connected and related,” Mandawe said.

“As a Cree learner, seeking out experiences like that as part of my training have been important. It needs to make sense to me in this way. It’s about our relationship to everything around us, and how we are all connected and related,” Mandawe said.

Coming into medical school, Mandawe had thought he would most likely end up in community practice. In his third year, he had a six-week external elective rotation in Chapleau, Ontario with Dr. Doris Mitchell, an Indigenous rural family physician. It showed him just how meaningful and important it was to have Indigenous physicians working in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

“I had an incredible experience with Dr. Mitchell’s team, and felt that I wanted to go out to the bush to help my community once I graduated,” he said. “I was happy and honoured to pursue this path, as I had so many inspirational mentors encouraging me to do this work.”

However, as third year unfolded, Mandawe found himself drawn to surgery and the operating room. He recalls telling close friends that he wanted to be a surgeon, and being met with bewilderment.

No one was more surprised by this than Mandawe, who says he spent a great deal of time meditating to understand this shift. “I’m not sure how the idea of wanting to go into surgery came into my mind and out of my mouth. But I was curious enough to pursue it.”

He says that he was drawn to surgery because in many ways, it resembled the land-based healing ceremonies that Mandawe grew up in, and his time learning to be a helper to people in those spaces.

“There was an undeniable parallel that I could not ignore, and the way I feel in the operating room is so similar to how I feel on the land in ceremony,” Mandawe said.

“When you are drawn to things, you have dreams about them. At the time, I wasn’t having dreams about the ceremonies that I grew up with, but I was having dreams about the operating room. I remember thinking, maybe the operating room is one of the ceremonies that I’ll walk with in this lifetime.”

“When you are drawn to things, you have dreams about them. At the time, I wasn’t having dreams about the ceremonies that I grew up with, but I was having dreams about the operating room. I remember thinking, maybe the operating room is one of the ceremonies that I’ll walk with in this lifetime.”

In March 2020, along with the rest of his class, Mandawe’s clinical learning was put on pause due to the COVID-19 pandemic. He worried about his community and the impact the pandemic would have on Indigenous people across the country, and began looking for ways to help. It wasn’t long before he was contributing to two research projects in support of Indigenous health and working as a contact tracer with the Middlesex-London Health Unit.

Ten months later, Mandawe felt even more confident in his decision to pursue surgery and satisfied that he knew where he was supposed to be.

“There is a certain kind of calm that you feel when you find flow in your life,” he said. “You know you’re on your path when you’re speaking your truth to the world around you, and people and opportunities start coming up.”

With steely determination, Mandawe listed Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery as his top choice for the match. He would be competing with hundreds of medical students for one of only 25 coveted spots across the country. He wanted to go all in and commit to the specialty, as this was the one he felt honoured his gifts, interests and vision as an artist.

He woke up on the morning of April 20, not yet knowing where he had matched. Once he received the confirmation email, reality began to set in. Sitting with the news, slowly, the weight of the past four years, the self-doubt, the sacrifices, the challenges and the beautiful experiences all came to bear.

“I cried for probably a half hour, letting the tears flow, in gratitude of all those who have added to my experiences up to this point; it was a beautiful moment that was really cathartic,” he said. “I knew this wasn’t just about me. It included all the people who are beside and around me, my parents, my grandparents, our elders, my community – everyone who has contributed to who I am today.

“My family has gone through so much institutional and interpersonal trauma and have made so many sacrifices. I’ve been fortunate to be able to pursue my passions and I feel lucky to have a mother and father who are kind, supportive and understanding.”

Mandawe had an opportunity to celebrate his achievements at Western’s Indigenous Student Graduation Celebration along with his medical school colleagues – who form a group at the School known as “A Tribe Called Med”.

Mandawe had an opportunity to celebrate his achievements at Western’s Indigenous Student Graduation Celebration along with his medical school colleagues – who form a group at the School known as “A Tribe Called Med”.

During the ceremony, Mandawe says students were acknowledged for the work they have done, what they attained, where they are coming from and the land-based knowledge systems and teachings that comes from their ancestors.

“It’s a beautiful way to celebrate Indigenous achievement and scholarship,” said Mandawe. “And it is particularly important for me as a grad.”

On June 5, Mandawe will join the members of the Medicine Class of 2021 for his medical school graduation. He’ll do so while planning his next journey to Halifax and Dalhousie University to begin his residency in plastic surgery.

The Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry congratulates Erik Mandawe and all the members of the Medicine Class of 2021 on their graduation.