The power and potential of collaboration

A successful research partnership focused on pregnancy and placental health demonstrates the benefits of working across disciplines and organizations

Emily Leighton, MA’13

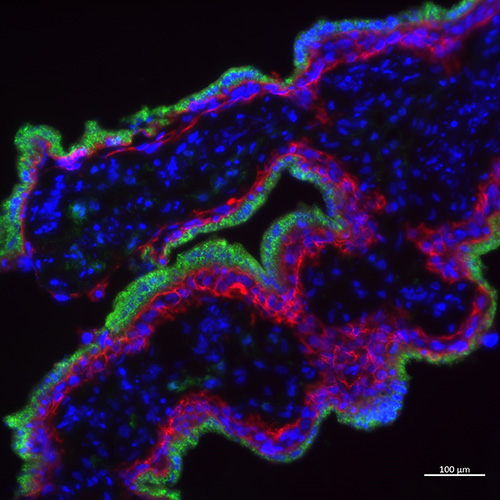

Image of immunofluorescence stain of a human placenta showing different trophoblast subtypes.

Image of immunofluorescence stain of a human placenta showing different trophoblast subtypes.

As a maternal fetal medicine specialist and expert in preeclampsia, Dr. Genevieve Eastabrook, Associate Professor, Obstetrics and Gynaecology, sees a lot of high-risk pregnancies in her work.

At times, it can be a frustrating vocation. Clinicians in the field have only a limited understanding of the pathophysiology underlying many of the pregnancy complications her patients experience.

“There are so many challenging clinical problems and it’s frustrating when we don’t have the right tools or the right answers,” she said.

This is what drives her interest in basic science research and has led to a unique, longterm collaboration with Stephen Renaud, PhD, a placental biologist and Associate Professor, Anatomy and Cell Biology.

Together, they are investigating potential biomarkers to predict and diagnose complications earlier in pregnancy and identify targets for treatment.

Renaud’s research program is focused on the placenta, an organ that acts as the interface between a pregnant person and their growing baby. “How the placenta functions sets us up for our entire lifetime; it’s not only an indicator of pregnancy health, but also individual health,” he said. “But it remains one of the least studied human organs.”

“We hope our discoveries will lead to better diagnostic tools to identify at-risk pregnancies, so all babies can get off to a healthy start.”

— Stephen Renaud, PhD

Pregnancy complications are often associated with the improper development or function of the placenta, including how and where it nestles into the uterus.

A placenta that burrows too deeply can result in placenta accreta, a serious condition that causes severe bleeding with attempted delivery of the placenta. If the placenta is too shallow, it can lead to inadequate delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the baby.

Renaud’s research team is looking at what regulates the ability of the placenta to nestle into the uterus. “We think the mother’s immune cells play an important role in controlling how deep the placenta burrows,” he explained.

With new funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Eastabrook, Renaud and co-investigator Jefferson Frisbee, PhD, are looking specifically at a protein called osteopontin.

Preliminary studies identified the protein as a promising regulator in the way the placenta develops. Using animal models to disrupt or promote osteopontin expression, the researchers are further exploring its function, as well as the role inflammation plays in its production.

“Looking at these types of molecular markers can tell us about the mechanisms around placental development,” Eastabrook explained. “From there, we can ask important questions such as: ‘Can we use the biomarker to predict or prevent complications? Can we improve treatments by understanding this process better?’”

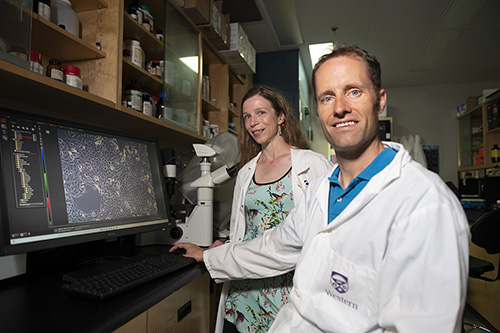

Dr. Genevieve Eastabrook and Stephen Renaud, PhD

Dr. Genevieve Eastabrook and Stephen Renaud, PhD

“We hope our discoveries will lead to better diagnostic tools to identify at-risk pregnancies, so all babies can get off to a healthy start,” added Renaud.

In the past seven years, Eastabrook and Renaud have collaborated on several projects. Their successful partnership demonstrates the power of collaboration in driving translational research.

“We’ll meet up and throw out some bold ideas and see if anything sticks,” said Eastabrook. “We also get lots of great ideas from students, residents and patients we work with. Having that collaborative approach and openness to new ideas is really important.”

For Eastabrook, carving out protected time for research amid her busy clinical schedule is challenging. Early on in her career, a mentor recommended she work with basic scientists who would support her active involvement in research projects.

Jefferson Frisbee, PhD, Chair, Medical Biophysics is a co-investigator on the project.

Jefferson Frisbee, PhD, Chair, Medical Biophysics is a co-investigator on the project.

“Often clinicians don’t have the time to set up and lead their own basic research programs, so building those trusted, long-standing relationships is essential,” she said. “It’s also important that we collaborate outside our clinical silos and be open to unexpected, unconventional opportunities.”

Working in different locations across the city can make it difficult for clinicians to get exposure to basic scientists and their research pursuits. Eastabrook hopes to see more formal and informal networking opportunities to facilitate productive research partnerships at the School.

“Our goal as researchers is to translate our findings to improve human health,” said Renaud. “By collaborating to study the mechanisms of disease at the basic level and better understand the clinical outcomes, we enhance the quality and creativity of our research.”