“ I had excellent exposure to the different aspects of medicine, a lot of one-on-one time with physicians and so much independent, hands-on experience. I feel way more confident and skilled than I did this time last year.”

“ I had excellent exposure to the different aspects of medicine, a lot of one-on-one time with physicians and so much independent, hands-on experience. I feel way more confident and skilled than I did this time last year.”

- Taylor McCann, third-year medical student

Emergency room closures. Not enough family doctors. Long drives to the nearest clinic. The health-care system in rural and regional communities faces serious challenges.

Working with its health-care partners across southwestern Ontario, Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry is doubling down on a strategy to place more medical learners than ever before in smaller communities for immersive local training experiences.

The model provides important lessons on how medical schools and communities can work together to train and build capacity in areas where physicians are in short supply. In the process, students get a comprehensive, top-tier education that only comes from real-world, hands-on experience.

Before breakfast on the second day of her rotation at Bluewater Health Sarnia, Taylor McCann delivered her first baby.

It wasn’t exactly a smooth birth — the umbilical cord was wrapped tightly around the infant’s neck.

As a third-year medical student gowned up in the delivery room for the first time, McCann would have been nervous if she had enough time to think about it. Instead, she focused on working hand-over-hand with the obstetrician who had told her moments earlier, “You’re going to deliver this baby.” Together they clamped and cut the cord, then carefully brought out the baby girl who rewarded them with a piercing cry.

“In school, we’d done simulations on dolls, but it’s nothing like the real thing,” McCann said of her training at Schulich Medicine. “You can learn all the theories, but every delivery is so different.”

2.3M

1 in 4

McCann should know. By the time she completed the six-week placement, she helped deliver 17 newborns — her knowledge and confidence growing a bit more after welcoming each infant into the world.

“It was amazing,” she said of her third-year undergraduate clerkship in Bluewater Health’s Obstetrics and Gynecology department, where she was the only undergrad student at the time working one-on-one with the obstetricians. “All the doctors were supportive and really excited about giving me as much hands-on practice as possible.

“Sarnia is an excellent place to get exposure and develop skills.”

“ I had excellent exposure to the different aspects of medicine, a lot of one-on-one time with physicians and so much independent, hands-on experience. I feel way more confident and skilled than I did this time last year.”

“ I had excellent exposure to the different aspects of medicine, a lot of one-on-one time with physicians and so much independent, hands-on experience. I feel way more confident and skilled than I did this time last year.”

- Taylor McCann, third-year medical student

“We know physicians often choose to work where they train because they put down roots. So, we are helping them put down roots in places that need doctors.”

“We know physicians often choose to work where they train because they put down roots. So, we are helping them put down roots in places that need doctors.”

—Dr. Victor Ng, BA Honors’04, MSc’05

Placing more doctors in hard-hit regions

Sarnia is also a place that desperately needs more physicians, especially in primary care, as it grapples with an escalating doctor shortage that is reaching crisis levels in similar and smaller cities and regions.

In Ontario, an estimated 2.3-million people don’t have a family doctor, according to the Ontario Medical Association. That number is expected to nearly double in the next two years, leaving one in four Ontarians without a family doctor by 2026, according to the Ontario College of Family Physicians.

In addition to primary care shortages, more staffing is needed in “generalist” specialties such as general paediatrics, psychiatry, pathology and general internal medicine in various communities across the province.

Nowhere is the problem more acute than in smaller- or medium-sized “regional and rural” communities.

In response to this challenge, provincial governments have added medical training seats at universities for more students and medical graduates to enter residencies. And in July, the federal government announced student loan forgiveness for doctors and nurses who choose to work in rural and remote communities.

Medical schools are also finding new ways to get doctors in the places that need them most.

For Schulich Medicine — which is working collaboratively with its health-care partners across southwestern Ontario to train nearly 1,000 students in clinical settings each year — part of the solution lies in giving more learners deep and meaningful training opportunities in rural and regional places.

With out-of-the-box thinking and mounting community support, more collaborations are emerging to attract more doctors to southwestern Ontario’s most hard-hit regions, including Sarnia.

“ We know it’s difficult for those who trained in Toronto or London to envision themselves moving to Woodstock or Sarnia or Chatham, but we also know from experience that people who train here often want to stay.” —Dr. Mike Haddad

“ We know it’s difficult for those who trained in Toronto or London to envision themselves moving to Woodstock or Sarnia or Chatham, but we also know from experience that people who train here often want to stay.” —Dr. Mike Haddad

School in a ‘unique position’ to help

“Every time we turn on the news, we see the need for health-care professionals — and as a medical school, we are in a unique position to help come up with a solution,” said Dr. Victor Ng, BA Honors’04, MSc’05, assistant dean of Distributed Education. “We know physicians often choose to work where they train because they put down roots. So, we are helping them put down roots in places that need doctors.”

Working with partners, the School has already developed two programs that will invite more students than ever to experience life and practice in smaller cities and regions.

In September 2025, eight third-year medical students will head to Sarnia’s Bluewater Health for their entire core clerkship as part of an immersive program that will double the number of students the following year. And paediatric residents from London will soon fan out into smaller communities where a sick child can mean an hours-long drive to the nearest emergency room.

Both programs aim to build on the School’s proven strength in providing rural and regional experiences to students. And they are drawing attention from alumni supporters who have come forward with much-needed funding.

“We know physicians often choose to work where they train because they put down roots. So, we are helping them put down roots in places that need doctors.”

“We know physicians often choose to work where they train because they put down roots. So, we are helping them put down roots in places that need doctors.”

—Dr. Victor Ng, BA Honors’04, MSc’05

A critical partner

With a population of 72,000, Sarnia is a friendly border city known for its waterfront park, golf courses, sandy beaches, marinas and boardwalk along Lake Huron. Downtown Christina Street is lined with quaint cafés , pubs and boutiques that are often bustling with residents and visitors.

“Sarnia is a great city — a hidden gem,” said Dr. Mike Haddad, Bluewater chief of staff and Schulich Medicine’s regional academic director for Lambton-Kent.

But it’s also a city where a growing number of people don’t have a family doctor, and many have started using the emergency department when they need primary care. For years, health practitioners, politicians and citizen advocates have been raising alarms about a doctor shortage that’s about to get worse with looming retirements.

“The aim is to expose more learners to a career in general pediatrics which is essential at a time when we are seeing a national shortage.” —Dr. Robin Mackin, assistant dean, Learner Experience and assistant professor, Department of Paediatrics

“The aim is to expose more learners to a career in general pediatrics which is essential at a time when we are seeing a national shortage.” —Dr. Robin Mackin, assistant dean, Learner Experience and assistant professor, Department of Paediatrics

Nearly half of the family doctors in Sarnia-Lambton are over age 60, according to Blue Coast Primary Care Recruitment and Retention, one of several groups working to recruit more doctors to the region.

“Everybody’s talking about it,” said 73-year-old Sarnia resident Marilyn Gifford, who collected more than 3,000 names on a petition demanding the province do something about the doctor shortage.

Bluewater Health has long been a critical partner for the School and one of its six regional teaching academies. More than 65 local physicians at Bluewater Health and Lambton County clinics already help train and mentor the School’s medical students and residents in Sarnia/Lambton as preceptors.

Clerkship is an MD student’s first real foray into clinical training, and typically, students — like McCann — complete these two years of training by rotating through several different specialities and regions.

Through the new immersive clerkship program in Sarnia, over two years, medical students will gain more in-depth experience in various Bluewater hospital departments, build meaningful relationships with staff and the community and develop a deep understanding of the region’s distinct health challenges.

The hope is that they’ll ultimately choose to remain in Sarnia.

“We know it’s difficult for those who trained in Toronto or London to envision themselves moving to Woodstock or Sarnia or Chatham, but we also know from experience that people who train here often want to stay,” Haddad said.

“ We know it’s difficult for those who trained in Toronto or London to envision themselves moving to Woodstock or Sarnia or Chatham, but we also know from experience that people who train here often want to stay.” —Dr. Mike Haddad

“ We know it’s difficult for those who trained in Toronto or London to envision themselves moving to Woodstock or Sarnia or Chatham, but we also know from experience that people who train here often want to stay.” —Dr. Mike Haddad

The plan builds on the success of the School’s partnership with Windsor Regional Hospital to launch a Windsor-Essex campus in 2008. Since then, there has been a 35-per-cent increase in family physicians in Windsor, and 31-per-cent increase in specialists.

While the need for more doctors persists, the training Schulich Medicine is delivering through the Windsor campus offers lessons for how medical schools and communities can work together to build capacity.

But setting up these immersive training programs comes with a price tag — from moving costs to travel and accommodation — and the School’s alumni community is stepping up to fill the gaps.

60

65

850

Donor moved by personal experience

For 25 years, Dr. Don Galbraith was on a first- name basis with his family doctor.

“It became a very personal relationship. Then he retired in his 70s,” said Galbraith, MD’61, a former faculty member at Schulich Medicine and an expert in child and forensic psychiatry.

Since then, primary care was precarious for Galbraith, who lives with his wife, Fay, on Lake Huron in Lambton County, Ont. For a while, there was no family doctor.

It was unsettling. It was also part of the reason Galbraith is committing more than $1 million to the School, with the majority providing critical support for the immersive Sarnia clerkship program.

Galbraith himself was previously director of Professional Education at Children’s Psychiatric Research Institute and medical director at St. Thomas Psychiatric Hospital, which included supervising clerkships.

“This program really clicked with me. I’m hoping it will excite students to stay in family practice,” he said.”

“It’s a desperate need. Any help we can give for programs like this is money well spent.”

$1-Million Gift

“This program really clicked with me. I’m hoping it will excite students to stay in family practice.”

—Dr. Don Galbraith, MD’61

$1-Million Gift

“If you work a month or two in a smaller community with other community care providers in health or education, you will see that this community has something to offer and it’s not just the medicine.”

—Dr. Richard Lubell, BA’63, MD’67, and Jan Lubell, MA’78

“ Ultimately, this program aims to cultivate a new generation of general paediatricians who are well- equipped to serve and understand the unique needs of our regional populations. We are very grateful to the donors who have made this vital program a reality and invested to elevate child health in our region.”

“ Ultimately, this program aims to cultivate a new generation of general paediatricians who are well- equipped to serve and understand the unique needs of our regional populations. We are very grateful to the donors who have made this vital program a reality and invested to elevate child health in our region.”

—Dr. Craig Campbell

‘It’s not just the medicine’

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, several regional hospitals have struggled to provide services for children. And when news reports said more than 2,330 children were on surgical wait lists in Ontario hospitals, staffing was identified as a major concern, particularly in smaller centres.

Historically, the emphasis in pediatric training has been on tertiary care patients, emergency care, chronic illnesses and subspecialty care. Recently there is a renewed focus on community-based paediatrics.

With the help of a $1-million gift from Dr. Richard Lubell, BA’63, MD’67 and Jan Lubell, MA’78, Schulich Medicine is planning to expand paediatric training opportunities in community settings.

“This gift is particularly fitting for us because it reflects our deeply held personal philosophies with respect to education and the importance of the larger community in which individuals and families live,” said Richard, who was chief resident at Toronto Sick Kids hospital before returning to London as a community-based paediatrician in 1973.

As well as having medical students in his office multiple days per week, he helped establish an after-hours community pediatric clinic to serve London and area children.

Jan played a key role in the development of community children’s services, including time as executive director of both Merrymount family support and crisis centre and Investing in Children, and as provincial designate for the development of early years policy and program development in London and surrounding area.

The soon-to-be expanded paediatric training program is designed to provide more immersive learning and teaching opportunities for paediatric residents in smaller community settings — where they may discover a lifestyle that resonates with their family’s needs and stay to establish a pediatric practice.

The Lubells observed that, “If you work a month or two in a smaller community with other community care providers in health or education, you will see that this community has something to offer and it’s not just the medicine.”

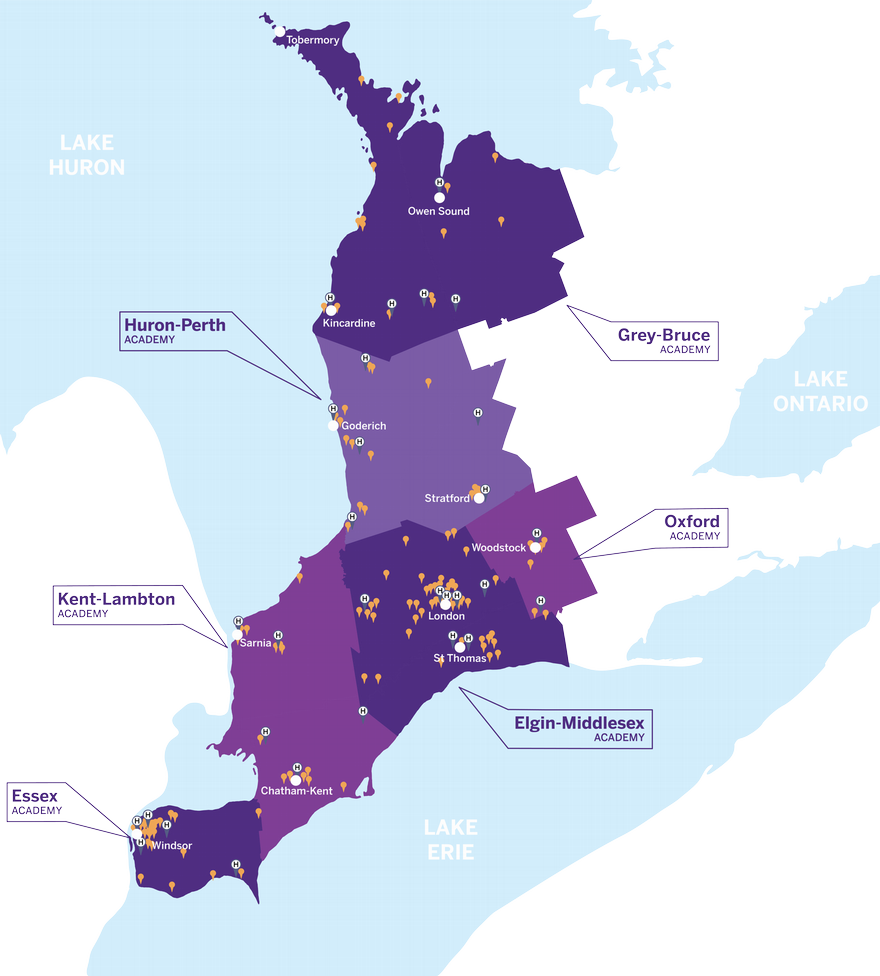

Currently, about 40 paediatrics residents are in various stages of a training program that includes short elective rotations in communities like Windsor, St. Thomas and Stratford. The plan is to develop a new, region-wide paediatrics training program, where residents will have the opportunity to live and practice across the whole region, from Owen Sound to Windsor.

“It’s an opportunity to see what the real depth and breadth of general paediatrics can be.” —Dr. Tamara Van Hooren, BSc’01

“It’s an opportunity to see what the real depth and breadth of general paediatrics can be.” —Dr. Tamara Van Hooren, BSc’01

The goal is to address the needs of both learners and communities, said Dr. Tamara Van Hooren, BSc’01, co-developer and program director for Schulich’s Paediatric Residency Program.

“We want to bring the voices of these communities to the development of the program,” said Van Hooren.

In rural and regional settings, paediatricians are “experts in everything, requiring a broad range of skills and expertise that allow them to manage patients from neonates to adolescents a far distance from a tertiary care centre,” she said.

“It’s an opportunity to see what the real depth and breadth of general paediatrics can be.”

Through full immersion, learners will be exposed to a diversity of paediatric career paths in regional centres, said program co-developer Dr. Robin Mackin, assistant dean, Learner Experience at Schulich Medicine, who has worked in Toronto-area community hospitals as well as rural and remote locations like Yellowknife and Inuvik, NWT.

“The aim is to expose more learners to a career in general pediatrics which is essential at a time when we are seeing a national shortage.” —Dr. Robin Mackin, assistant dean, Learner Experience and assistant professor, Department of Paediatrics

“The aim is to expose more learners to a career in general pediatrics which is essential at a time when we are seeing a national shortage.” —Dr. Robin Mackin, assistant dean, Learner Experience and assistant professor, Department of Paediatrics

“The aim is to expose more learners to a career in general pediatrics, which is essential at a time when we are seeing a national shortage,” said Mackin.

Placing paediatric residents in diverse settings across the region provides them with comprehensive training and exposure to a variety of paediatric practices, said Dr. Craig Campbell, Children’s Health Foundation Chair in Paediatrics Research and head of the Department of Paediatrics at Schulich Medicine and Children’s Hospital LHSC.

“Ultimately, this program aims to cultivate a new generation of general paediatricians who are well-equipped to serve and understand the unique needs of our regional populations. We are very grateful to the donors who have made this vital program a reality and invested to elevate child health in our region,” he said.

“ Ultimately, this program aims to cultivate a new generation of general paediatricians who are well- equipped to serve and understand the unique needs of our regional populations. We are very grateful to the donors who have made this vital program a reality and invested to elevate child health in our region.”

“ Ultimately, this program aims to cultivate a new generation of general paediatricians who are well- equipped to serve and understand the unique needs of our regional populations. We are very grateful to the donors who have made this vital program a reality and invested to elevate child health in our region.”

—Dr. Craig Campbell

“ When students get to communities like Chatham or Sarnia or smaller towns, they realize quickly the impact they can have, and they want to return. Rural and regional hospitals often have the most complex and sick patients in the province, and you get to save people’s lives because of that.” —Dr. Shawn Segeren, MD’16

“ When students get to communities like Chatham or Sarnia or smaller towns, they realize quickly the impact they can have, and they want to return. Rural and regional hospitals often have the most complex and sick patients in the province, and you get to save people’s lives because of that.” —Dr. Shawn Segeren, MD’16

‘You get to save people’s lives’

“Once you’re in a smaller community, you realize the value you can bring as a physician,” said Dr. Shawn Segeren, MD’16, an emergency medicine physician at Chatham-Kent Health Alliance, which serves more than 100,000 people.

Smaller centres make it easy for new physicians to get to know other doctors, staff and patients. They start to form connections inside and outside the hospital, which opens doors for them to become “change leaders,” he said. “When students get to communities like Chatham or Sarnia or smaller towns, they realize quickly the impact they can have, and they want to return,” he said. “Rural and regional hospitals often have the most complex and sick patients in the province, and you get to save people’s lives because of that.”

“ When students get to communities like Chatham or Sarnia or smaller towns, they realize quickly the impact they can have, and they want to return. Rural and regional hospitals often have the most complex and sick patients in the province, and you get to save people’s lives because of that.” —Dr. Shawn Segeren, MD’16

“ When students get to communities like Chatham or Sarnia or smaller towns, they realize quickly the impact they can have, and they want to return. Rural and regional hospitals often have the most complex and sick patients in the province, and you get to save people’s lives because of that.” —Dr. Shawn Segeren, MD’16

Fellow alum Dr. Noranda Nyholt, MD’08, said her experience in regional health care was life-changing and led to her decision to set up a practice in Sarnia.

“They were excited to have me there. They wanted to show me stuff, to teach me, and I got to do procedures that I would have had to wait in line to try at bigger hospitals,” she said. “It was amazing.”

After graduation, she moved to a group practice in Belleville for a few years, then made her way back to Sarnia in 2016. With Bluewater Health only a four-minute drive or 15-minute walk from her office, she makes good use of her hospital privileges.

“If one of my patients gets sick, I continue their care in the hospital. If someone has a baby, I go up and see the new baby – it’s the best part of the job.”

Like Segeren, Nyholt believes exposing students to the Lake Huron community will “100 per cent” inspire them to stay.

“Smaller centres can be a hard sell for people who don’t know them,” she said. “But there is so much opportunity here. The hospital is vibrant, there are great specialists and I feel well-supported.”

“Besides,” she said, “It’s lovely here.”

For one thing, there are her daily runs along the boardwalk. And her kids get that same view of Lake Huron right out their classroom window — “Can you imagine that?

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t say, ‘Man, am I lucky.’”

1,000

Schulich Medicine learners complete hands-on clinical learning at health-care partner sites in60-PLUS

communities, from Windsor to Tobermory.

Answering the call to help back home

Growing up in Parkhill, Ont., a community of 7,000 that’s about a 40-minute drive from London, McCann knows first-hand what the small-town doctor shortage feels like.

“My whole motivation for going to medical school was seeing my grandparents unable to get a family doctor after theirs retired,” she said.

It wasn’t until her clerkship rotations in Chatham, Listowel and Sarnia that McCann realized how fulfilling it would be to work in a smaller centre.

Maybe it was the countless joint injections in Listowel. Or the IUD insertions, and endometrial biopsies. Or the meaningful conversations with psychiatric patients in Chatham.

And of course, there were the 17 newborns McCann caught at Bluewater — “They deliver a lot of babies in Sarnia,” she said with a laugh.

“It helped me see the value I would have as a doctor in a smaller community,” she said. “I had excellent exposure to the different aspects of medicine, a lot of one-on-one time with physicians and so much independent, hands-on experience. I feel way more confident and skilled than I did this time last year.

“I can see myself working in rural medicine. I’m excited about it.”