From pencil sketches to high tech

Neurosurgeon Dr. Victor Yang likes to draw and nearly all of his more than 78 patents for medical devices started out as pencil sketches on paper.

Neurosurgeon Dr. Victor Yang likes to draw and nearly all of his more than 78 patents for medical devices started out as pencil sketches on paper.

A prolific inventor with a talent for drawing, Dr. Victor Yang has created numerous technology and knowledge transfer successes.

For example, Yang led a team of scientists and doctors to develop the 7D surgical navigation system, which provides image-guided assistance for craniospinal surgeries. He also developed optical tomographic devices for skin cancer imaging. These innovations have turned into commercial products and been adopted by many hospitals and clinics around the world. He’s now working on microcatheters and robotic devices that will assist in performing complex surgeries.

He grew up writing Chinese calligraphy and his grandparents were quite strict that he got it right. Plus, when he did his engineering undergraduate degree, his was the last class required to do drafting by hand before drafting software came into vogue.

While he has no formal art training, two things help the professor of Neurosurgery, Medical Imaging, Orthopedic Surgery and Medical Biophysics in the Department of Clinical Neurological Sciences take his ideas from sketches to high-tech innovations.

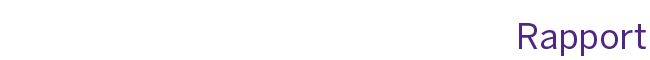

Four years ago, Yang switched from pencil and paper to an electronic tablet but the kind that simulates the physical aspects of drawing. He uses an electronic pencil and the feel of it on the pad is “scratchy” just like it would be on paper. He makes sure to always have the tablet close by – just in case an idea comes to him.

But Yang finds stepping away is just as important to the creative process. “Days will go by and I haven’t updated a drawing. It will drive me crazy,” he said. “That’s when I know it’s time just to sit on the deck.”

Surrounding himself with people who understand him and who can help refine ideas is also part of his creative process. Yang’s wife Jenny, with a background in biotechnology business administration, was instrumental in helping him refine his first impactful grant proposal during a week-long neurosurgery research retreat they spent in Woods Hole Marine Biology Lab, Massachusetts.

Wandering around the marine research labs, they were captivated by drawings of sea creatures as viewed under microscopes.

“Sea stars have little tentacle-like feet they use to move around,” said Yang. “They’re about the size of the microcatheters we use to go into the brain to deal with blood vessel disorders.”

So, crammed into their single dorm room bed each night, the couple hashed out a proposal to build a soft, minimally invasive robotic-like catheter that could move by itself.

“And guess what? With collaborators at the University of British Columbia and the University of Toronto, the project was funded for a quarter of a million dollars,” he said, shaking his head.

“It turns out this project was incredibly difficult. The starfish is an ancient creature and we are not gods,” he said. “It was a fascinating project but it was not yet mass manufacturable. But I let my creativity run free and I learned a lot and it established my credibility as a researcher.”

Balancing effort with letting go

Psychiatrist Dr. Elizabeth Osuch, a professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, has a strategy that will resonate with anyone who has ever hit a creative brick wall.

Psychiatrist Dr. Elizabeth Osuch, a professor at Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, has a strategy that will resonate with anyone who has ever hit a creative brick wall.

“Some of our most challenging problems get solved when we’re not trying to solve them,” she said. “The brain is an interesting organ. It still works on stuff even when you’re not consciously thinking of it.”

Osuch conducts brain imaging to identify biomarkers for mood and anxiety disorders in youth so that she can match those disorders to the most effective class of medication. That may sound straightforward but it isn’t.

“People have done functional brain scans of psychiatric patients for decades now and not a single clinical change has resulted from any of that work,” she said. “Millions of dollars have gone into this and it’s very frustrating.”

Yet she and her team persevere, combining brain imaging with artificial intelligence tools to predict who needs a mood stabilizer and who needs an anti-depressant. Their preliminary research suggests it can be done but large-scale clinical trials will be necessary to prove it.

Much of Osuch’s strategy for generating both inspiration and perseverance involves working intensely on a problem and then stepping away. She finds being in nature hugely helpful but not in a direct way. Mostly, it’s because it grounds her. Living with easy access to a forest, being in nature can mean something as simple as gazing out her window at the greenery or working in her garden.

It helps her to be open to inspiration, whenever and however it comes. “I usually have brilliant ideas at three or four in the morning when I wake up between sleep cycles,” she said. “I think, ‘Oh yeah, I should try that.’”

Osuch never writes down her middle-of-the-night insights. She simply trusts that, if it’s a good one, she’ll remember it in the morning.

One size does not fit all

Endocrinologist Dr. Rob Hegele finds the act of writing helps him think more creatively.

Endocrinologist Dr. Rob Hegele finds the act of writing helps him think more creatively.

Given that he and his lab have pinpointed the genetic causes of more than 25 diseases and he has published more than 930 papers, cited more than 83,000 times in the medical literature, it’s clearly an effective strategy for him.

Sometimes Hegele will write by hand on a piece of paper attached to his clipboard – he has a pen he’s had since high school that he likes to use. Other times he opts for his laptop. Either way, he can find himself in what psychologists call a flow state, where he becomes completely immersed in his work without noticing time passing.

“When I write, I notice that spark more. I don’t know where it comes from, but the physical act of writing seems to help,” said Hegele, Distinguished University Professor of Medicine and Biochemistry. “I can be sitting in the hospital library writing when I look up and suddenly realize it’s 5 p.m.”

That said, Hegele prefers to write in the morning, when his ideas can be three times more effective and clearer than at any other time of day. The process of putting his writing aside for a day or two and coming back to it to revise also helps him sharpen creative ideas.

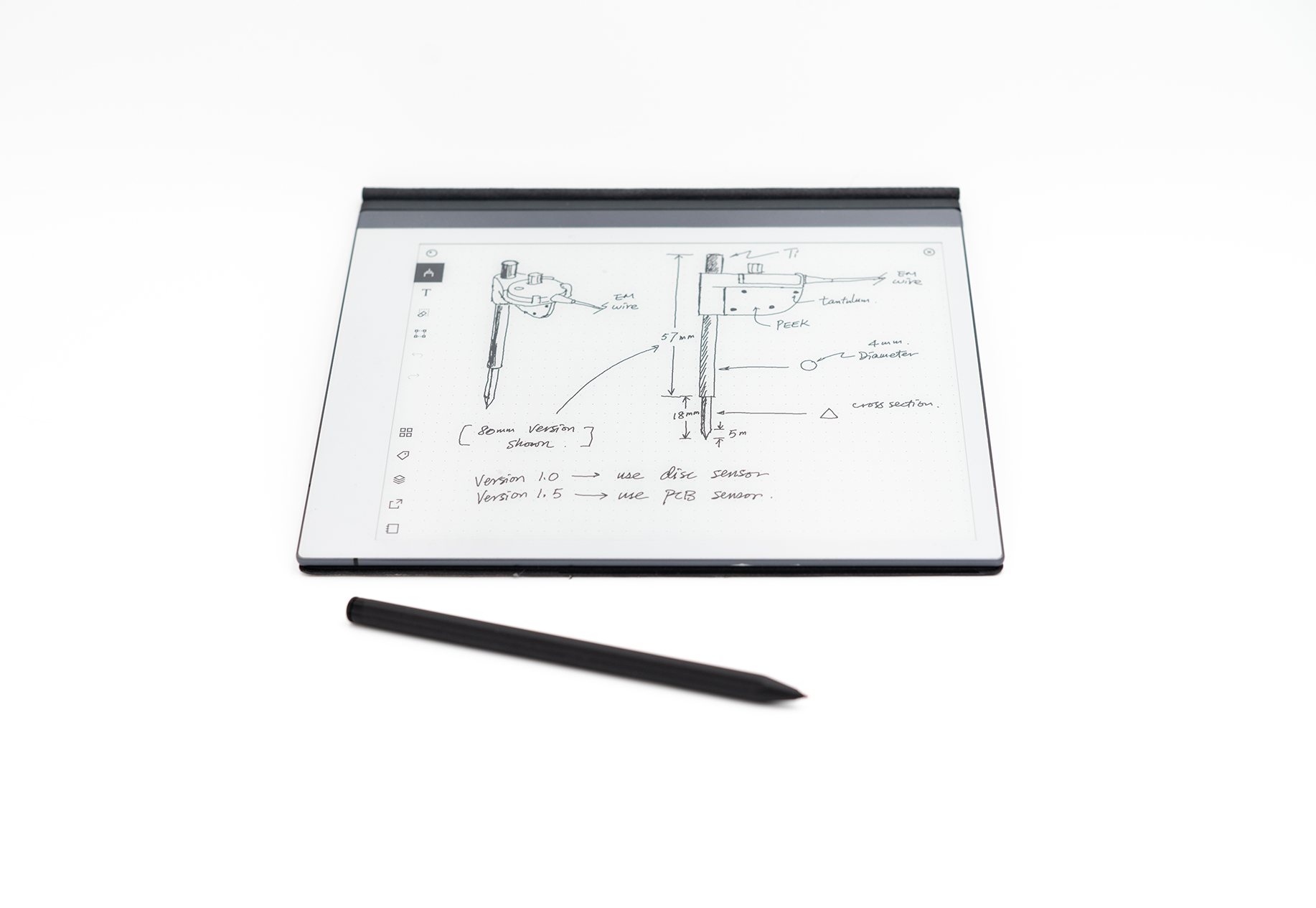

Hegele is an accomplished piano player, which informs the way he generates big ideas in his research. Making music, he said, requires him to be creative while following strict rules with respect to harmony and counterpoint. It’s a lot like writing a grant proposal where there are strict rules, yet you must come up with something original within those rules, he said.

“Your ideas are going to be reviewed by an anonymous star chamber in Ottawa so your application has to stand out,” he said. “Of course, the pressure to raise money tends to focus the mind,” he added with a laugh.

While he makes good use of the latest technology in his genetic research, Hegele insists on a simple flip phone because he doesn’t have the willpower to resist the internet in his pocket. It would only distract him from the priorities he has set for himself.

Hegele stands firm on this point, even to the point of enduring others’ ribbing. Once, after giving a talk to an Amish community near London about genetics and heart disease, his phone rang. When he pulled it out, people started giving him a hard time: “They said, ‘Is that a flip phone? Aren’t you a doctor?’ I was mocked by the Amish.”