Planning for the next pandemic

How can the COVID-19 experience help prepare society for the next pandemic? Researchers are examining patterns throughout disease history, identifying barriers to research, and undertaking proactive vaccine development to find out

By Alexandra Burza, MMJC’19

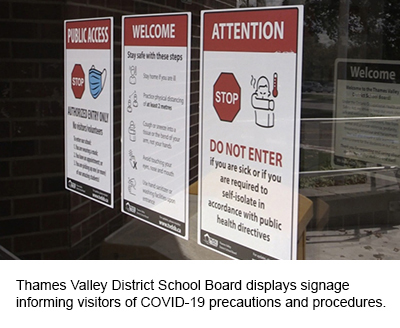

Infection rates, lockdowns, mask mandates; once foreign, these concepts have permeated our public consciousness, dominating politics, headlines and our everyday lives as we navigate the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

While often described as unprecedented, Professor Shelley McKellar, Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine, says that couldn’t be further from the truth. Examining comparable disease outbreak events throughout Canadian history shows significant parallels to what the world is experiencing today, offering a glimpse into what our future may hold.

“There is always going to be a new pathogen; a next pandemic. When it happens, we look to our past pandemics to see what we can do differently and what has been successful,” McKellar said.

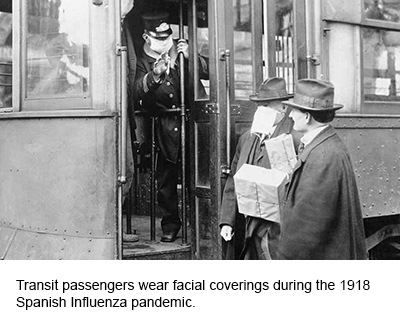

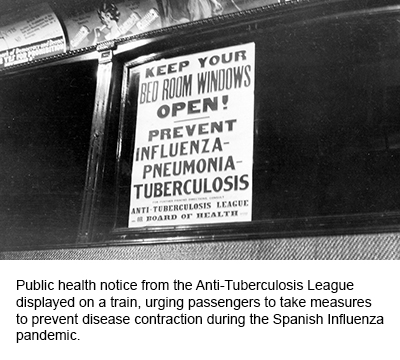

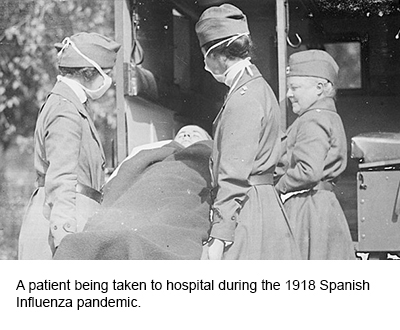

During the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, which had a similar local impact in terms of infection rates to COVID-19 today, strategies such as mask wearing and business closures were commonly enforced in Canada. Even remote learning is not a novel concept; during the polio outbreak in the 1930s, Canadian school children completed their studies thanks to lesson plans shared in daily newspapers and in radio broadcasts.

During the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, which had a similar local impact in terms of infection rates to COVID-19 today, strategies such as mask wearing and business closures were commonly enforced in Canada. Even remote learning is not a novel concept; during the polio outbreak in the 1930s, Canadian school children completed their studies thanks to lesson plans shared in daily newspapers and in radio broadcasts.

“When the science wasn’t there for us, there were these traditional tools – non-pharmaceutical interventions that we know have an impact,” McKellar explained. “Especially after the 1918 Influenza pandemic, people started to see the value of government taking a role in disease management. But public health is a tricky thing because it cannot so much be innovative as it is reactive.”

The Public Health Agency of Canada was established in direct reaction to the 1918 pandemic, which emphasized the need for a co-ordinated national strategy for health information dissemination. In this same way, each significant epidemiological event exposes new opportunities and threats to public health implementation and science communication, and strategies evolve in response to the lessons learned from that particular disease context.

For Art Poon, PhD, Associate Professor, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the most significant issue that has come to light during the course of the pandemic has been inconsistencies in access to epidemiological data. Along with members of his lab, Poon has been developing an interactive tool that analyzes global COVID-19 data and displays the information for public access.

For Art Poon, PhD, Associate Professor, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, the most significant issue that has come to light during the course of the pandemic has been inconsistencies in access to epidemiological data. Along with members of his lab, Poon has been developing an interactive tool that analyzes global COVID-19 data and displays the information for public access.

“The initial response was very strong; many laboratories geared up to sequence samples of the virus that had been collected from across the country,” Poon explained. “There was an opportunity at that early stage to use this data to characterize transmission and make data-driven policy decisions. However, in many jurisdictions, that data was not shared. We need to have better integration between public health and thescientific community in Canada.”

Since the establishment of the Canadian Data Portal in May 2021, access to data has improved Poon says, but in the crucial early days of the pandemic he and other researchers felt limited in their contributions to the COVID-19 response. He also emphasized the need for more expertise within his area of research – bioinformatics.

“We’ve been trying to address this gap in expertise by training the next generation to work with and build tools to deal with future health challenges.”

Poon was part of efforts to establish a new undergraduate training program in medical bioinformatics at the School, which has been approved this year.

The pandemic’s exacerbation of inadequacies related to funding, expertise and resources is common for these types of events, McKellar says, and with greater attention comes a desire fromthe public and government to rectify these issues. But history has demonstrated that society often falls into what she calls a ‘panic and neglect’ cycle.

The pandemic’s exacerbation of inadequacies related to funding, expertise and resources is common for these types of events, McKellar says, and with greater attention comes a desire fromthe public and government to rectify these issues. But history has demonstrated that society often falls into what she calls a ‘panic and neglect’ cycle.

“When we’re in the throes of a disease outbreak, there is a sense of being under siege. Why is the government not invested in vaccine manufacturing? Why are our long-term care facilities so egregiously understaffed? And then when things calm down, whether it be a new government or new problems come onto our plate, somehow it gets moved lower down the list.”

Successfully breaking the cycle depends on the severity of the event; the more disruptive a pandemic is, the more significance it holds in the collective public memory. During the 2003 SARS pandemic, the average Canadian was fairly removed from the pandemic experience, with most outbreaks occurring in hospitals. In countries such as Singapore where the impact to the public was more significant, that pandemic experience resulted in cultural shiftssuch as the adoption of mask-wearing in public places.

This ultimately helped mitigate the severity of the COVID-19 experience in the country. For Canadians, McKellar believes the scale of disruption and severity of outbreaks with this pandemic have been significant enough to catalyze change.

At Western’s Imaging Pathogens for Knowledge Translation (ImPaKT) Facility, Ryan Troyer, Assistant Professor, Microbiology and Immunology and his colleagues have already begun work to proactively prepare potential vaccines for future coronaviruses.

“We’ve recognized that there needs to be a greater investment in preparing vaccines in advance for the most likelyviruses that may emerge. Between pandemics, this has been a very neglected area of research and I think we can do better than that,” he said, adding that an investment in domestic vaccine manufacturing capacity is also crucial to this work.

“We’ve recognized that there needs to be a greater investment in preparing vaccines in advance for the most likelyviruses that may emerge. Between pandemics, this has been a very neglected area of research and I think we can do better than that,” he said, adding that an investment in domestic vaccine manufacturing capacity is also crucial to this work.

In collaboration with biologists and the Royal Ontario Museum, the ImPaKT Facility is using thousands of tissue samples from bats to identify what coronaviruses they carry and which are transmissible to humans. Then, using the spike proteins from viruses with pandemic potential, Troyer and his colleagues can sequence their genetic information to develop vaccines.

Troyer says that the connection between the increasing prevalence of zoonotic diseases and ecological exploitation by humans cannot be ignored. With an increasing encroachment of human activity on wildlife and natural spaces, spurred by urbanization and climate change, the risk of disease is heightened.

While much is still uncertain about how the COVID-19 experience will impact the path forward, and how we will negotiate the limitations it exposed, McKellar says what we can count on is society’s resiliency and scientific innovation.

“Looking at pandemics in the past 200 years, there have been lots of changes, but lots of continuity and innovation; society always finds a way to rebound and rebuild.”